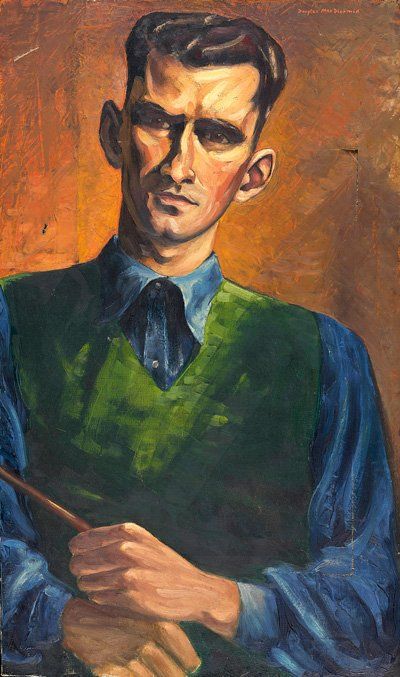

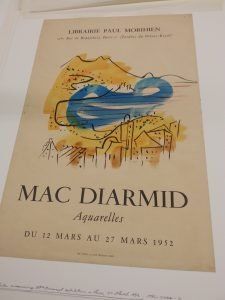

One of New Zealand’s most acclaimed expatriate painters, Douglas MacDiarmid, died in Paris on 26 August 2020, aged 97, after a long and unconventional life.

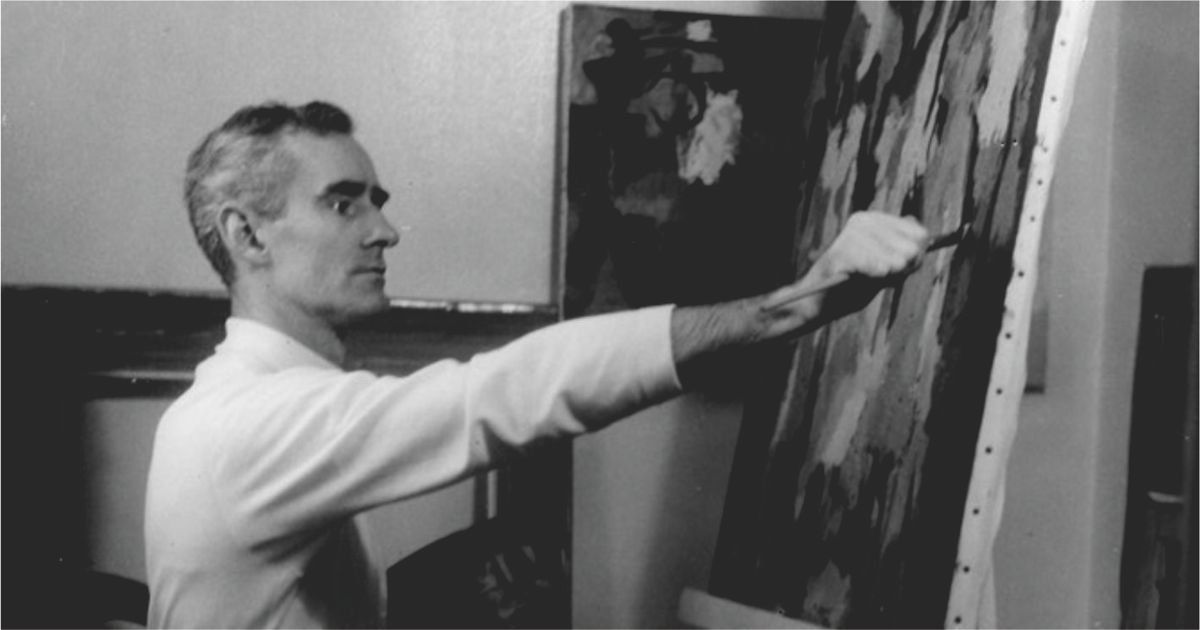

Celebrated for his diversity of approach and mastery of colour, he overcame hardship and tragedy to forge a successful career in France over seven decades as a highly collectable painter on the demanding European art scene. Indeed, he continued to paint daily, pushing new creative boundaries and exhibiting regularly into his nineties.

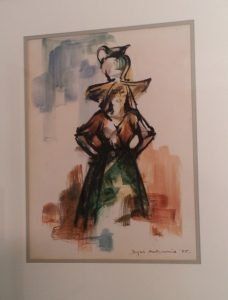

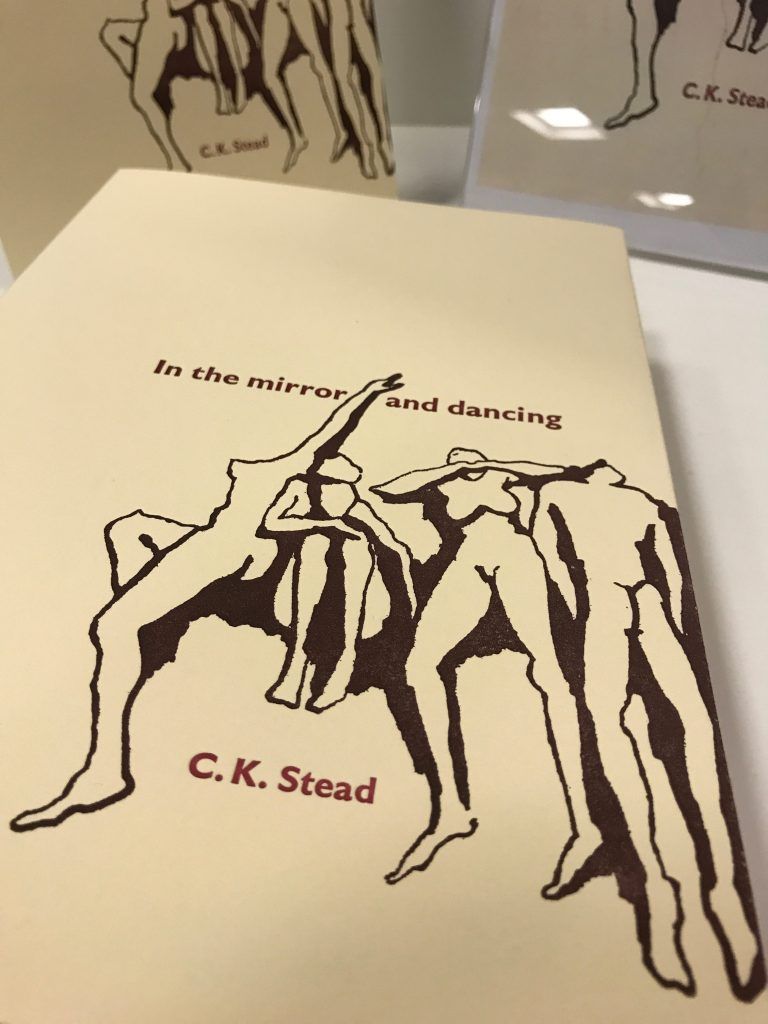

MacDiarmid always refused to be labelled or classified, except to admit he was an ‘expressionist’ painter – “one who expresses the visual rhythm of things”. He was widely interested in classical music, literature, ancient history and mythology, and fascinated by people and the ‘human condition’, as well as the beauty and sensuality of the body, all of which imbued his work.

What interested him most, as he simultaneously created landscape, portrait, figurative, abstract and semi abstract paintings, was not visual description but the tantalising essence of what lay underneath. Uninterested in fame or fortune, he kept his prices modest in the belief that art should be accessible to all, and his paintings must “live where they are loved”.

From small town New Zealand, to the world

Douglas Kerr MacDiarmid was born in Taihape, New Zealand, on 14 November 1922, the second son of Dr Gordon and Mary MacDiarmid. As a child, he attended Taihape Primary School and, after a year boarding at Huntly Preparatory School in Marton, spent the rest of his secondary education as an unruly boarder at Timaru Boys High School, considered the finest boys’ school in New Zealand at the time.

Growing up in a household full of books, poetry, music, Douglas wanted to be an artist, a writer and a concert pianist. Desperate to break free of family and inner turmoil, he found himself in paint.

The early 1940s, and war years, were spent in Christchurch where he went to university at Canterbury College, gaining an arts degree in music, English literature, languages and philosophy, and did his home force military service. Christchurch was the place where he came alive in the company of an extraordinary network of older creative luminaries such as Frederick and Evelyn Page, Rita Angus, Ngaio Marsh, Leo Bensemann, Theo Schoon, Allen Curnow, as well as the first great love of his life, composer Douglas Lilburn. Inspired by these willing mentors, he was soon exhibiting with The Group, and steadfastly continued to do so for a decade after he left New Zealand.

Once shipping routes were restored after World War II, Douglas headed overseas to “devour the world”, sailing out of Lyttleton in July 1946 for London, initially as tutor to his Christchurch landlady Blanche Harding’s youngest son on the long sea voyage. He returned home three years later with a very different horizon but stayed barely a year.

In 1951, he settled permanently in France, periodically coming back to New Zealand for exhibitions and to visit family. “I wanted a land with something to say through its physical evolution, how people had lived. I wanted to make contact with the long history of our thought-processes and words. I had no choice but plunge into the living, multiple, tumultuous continuity of the Mediterranean, which, without seeing it happen, became my second home,” he said. “Becoming part of this experience is one thing, but you don’t snakelike cast off your former skin.”

Travelling widely, ranging free

His life was an endless adventure. A bisexual man who had to leave his home country to live life on his own terms; the deliberately untrained painter was determined to make his name in art. An audacious, inquisitive spirit, he overcame the odds to become one of New Zealand’s most engaging cultural ambassadors abroad while barely being recognised at home.

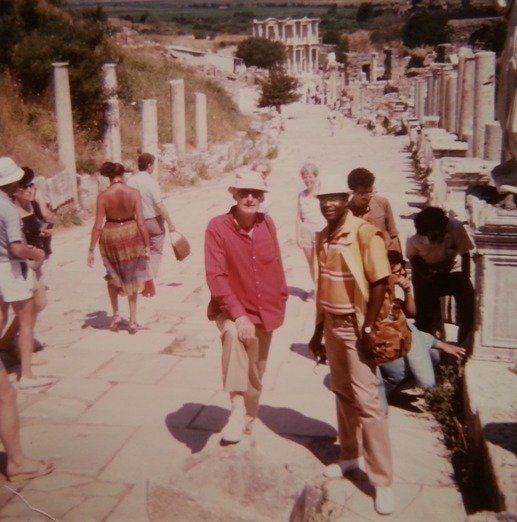

MacDiarmid travelled extensively to nourish his creativity whenever he had two coins to rub together, sharing many journeys with Patrick, his beloved partner of more than 50 years, into old age. The pair had a passion for clambering over archaeological ruins across the Mediterranean and further afield to satisfy their curiosity about the world and its origins. They escaped Paris winters at Bailiff, Patrick’s birthplace on the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe in the French West Indies, where they built a little holiday house.