A lingering glimpse inside Rue Cavallotti, 2004

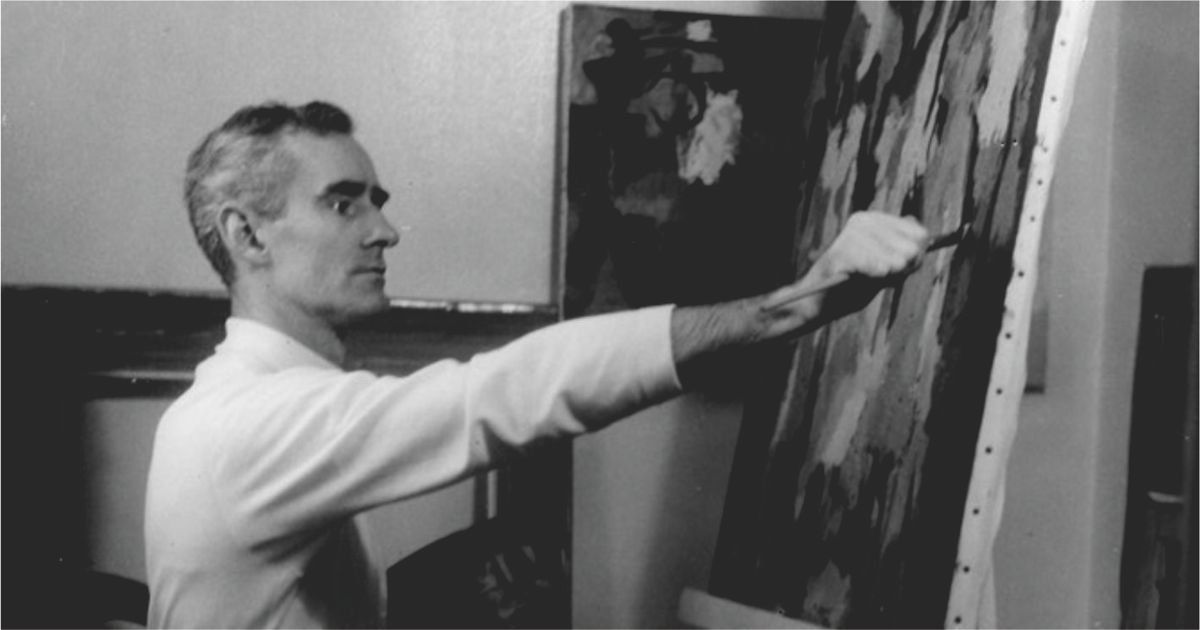

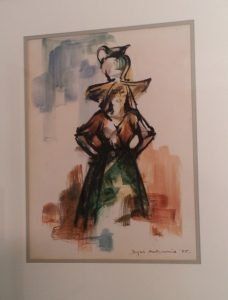

In October/November 2004, Home and Entertaining New Zealand magazine published a four-page feature article on Douglas MacDiarmid, his paintings and equally colourful and stylish personal surroundings. He was an exuberant 82 at the time, still at the top of his game – experimenting and pushing creative boundaries.

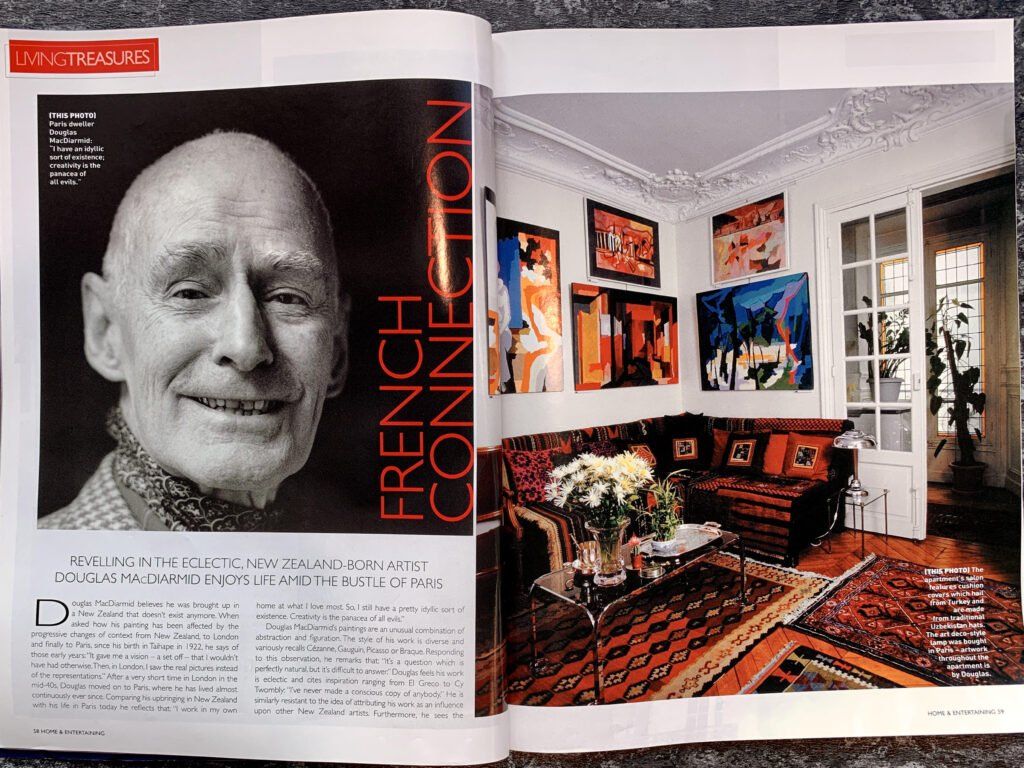

The interior of Douglas and Patrick’s Montmartre apartment has changed little since that time…a different spread of paintings but essentially the same elegant aesthetic. Every year or so from 1992 to 2014, the hallway, living room and studio of this welcoming home was converted into an exhibition gallery for a few days (Chez lui) to show his latest work. The intimate, informal atmosphere of these home shows were occasions dedicated collectors, friends and newcomers eagerly looked forward to – a chance to look behind the scenes, chat to the painter at ease in his own setting and see where Douglas created his visions.

Here is the full transcript of that article…

FRENCH CONNECTION

REVELLING IN THE ECLECTIC, NEW ZEALAND-BORN ARTIST DOUGLAS MACDIARMID ENJOYS LIFE AMID THE BUSTLE OF PARIS

Douglas MacDiarmid believes he was brought up in a New Zealand that doesn’t exist anymore. When asked how his painting had been affected by the progressive changes of context from New Zealand, to London and finally to Paris, since his birth in Taihape in 1922, he says of those early years: “It gave me a vision – a set off – that I wouldn’t have had otherwise. Then, in London, I saw the real pictures instead of the representations.” After a very short time in London in the mid-40s, Douglas moved on to Paris, where he has lived almost continuously ever since. Comparing his upbringing in New Zealand with his life in Paris today he reflects that: “I work in my own home at what I love most. So, I still have a pretty idyllic sort of existence. Creativity is the panacea of all evils.”

Douglas MacDiarmid’s paintings are an unusual combination of abstraction and figuration. The style of his work is diverse and variously recalls Cézanne, Gauguin, Picasso or Braque. Responding to this observation, he remarks that: It’s a question which is perfectly natural, but it’s difficult to answer.” Douglas feels his work is eclectic and cites inspiration ranging from El Greco to Cy Twombly: “I’ve never made a conscious copy of anybody” He is similarly resistant to the idea of attributing his work as an influence upon other New Zealand artists.

![Home and Entertainment Magazine article about Douglas MacDiarmid Page 60 interior and street view captions: (Clockwise from left) Douglas’s apartment building was built around 1888 during the period of the French Belle Epoch. Built on the side of the first hippodrome (race track) in Paris, it is built on a curve, so there are no square angles in the building; the second bedroom boasts a Louvre copy of the head of the Egyptian god Osirus’ the apartment in Rue Cavallotti is 108 square metres – a large flat by Parisian standards; the artist considers a bronze bust of his younger self, created in 1962 by Prix de Rome winner, sculptor Jean Dambrin. The work was swapped for a painting. […after the two exhibited together] Page 61: (top left) Douglas keeps his paint mixtures in film canisters, so he does not lose the mixed tint. The figure is of the Egyptian god Anubis, bought in Aswan, Egypt. (Top right): The dining room area features original Eero Saarinen Tulip chairs, bought from Knoll, the stockists of Saarinen furniture in Paris in the 70s. Douglas firmly believes these designs are classics. (Bottom left): Along from the Dambrin bronze stands a statue of an ancestral figure from Central Africa and a wooden mere from the mid-North island, dating from the late 19th century. The influence of these objects is shown in Douglas’s work.](https://lirp.cdn-website.com/952bb7bb/dms3rep/multi/opt/HENZ-Oct-2004_Living-Treasures-P60-61-1024x768-1920w.jpg)

Furthermore, he sees the attempts of modern and contemporary New Zealand artists to invent a new style as self-conscious.

“It’s a constant source of dismay to me,” he says, preferring to believe that an understanding of cultural history will give rise to a natural evolution in artwork. Using his Parisian setting as an analogy, he describes Rogers’ and Piano’s architecturally revolutionary Centre Pompidou as an example of “a loathsome tendency – I don’t admire it at all.”

“I find it difficult to talk about pictures, because what you see is all there is,” remarks Douglas when asked about the use of outlines in his landscapes. “I have a very poor sense of reason, but a very strong sense of feeling.” The use of outlined areas in otherwise reasonably detailed paintings can be seen as analogous to the depth of field to a photograph. Douglas focuses sharply on his subject and backgrounds the remainder of the image through abstraction. Conversely, some of his portraits display a complete even-handedness of detail from subject to background, and so highlight relationships between one and the other. While the vast majority of his work is painting, the hallway of Douglas’ home displays a sculptural work in polyester. The piece is inspired by the Paris Metro and its incised and extruded cubic forms recall the work of Spanish abstract sculptor Eduardo Chillida.

“There is only one thing to do – have things that you love,” says Douglas of the diverse range of furniture that fills his apartment. While most of the spaces are covered with richly coloured and textured rugs, cushions and other objects that he has collected in his travels, a white plastic pedestal table and Tulip chairs by Eero Saarinen take pride of place.

His home sits within a typical Parisian block, with parquet floors and tall windows that open to floor level to frame views of a bustling multicultural streetscape. Designed as miniature versions of a grand French chateau, Parisian apartments are often filled with doors to create an illusion of space. Douglas has covered over many of these doors to provide more useable space and the walls of his living room have been fitted with brackets to hang screens over his belongings when he exhibits his work at home.

![Home and Entertainment Magazine article about Douglas MacDiarmid Page 62: (top) Douglas’s love of colour, introduced against a neutral background in the form of artwork, is evident in his bedroom. [Biographer’s note: This is in fact his partner Patrick’s bedroom, the walls lined with paintings from their life together] (Bottom): The spare room is full of Douglas’s own paintings, books and objects collected over a lifetime of travelling. [Biographer’s note: This is Douglas’ bedroom. The three small portraits on the right wall are of his parents Mary and Gordon MacDiarmid. Douglas may have left this world but these personal paintings remain there as always.]](https://lirp.cdn-website.com/952bb7bb/dms3rep/multi/opt/HENZ_Living-Treasures-P62-768x1024-1920w.jpg)

New Zealand has a long history of loss of intellectual wealth through migration. While it could be argued that this trend of “brain drain” has slowed in the post-September 11 world, more fundamentally the effect of this phenomenon has lessened, or even reversed, with changing patterns of travel and information technology. Large numbers of New Zealanders overseas now contribute to and enrich their home country’s culture during their absence, owing to the intimate engagement with other settings that this allows. Douglas has not travelled back to New Zealand frequently during his nearly six decades of absence and he is not a user of the internet or e-mail. [Biographer’s note: he later became computer-savvy, and continued to email and digitally upload photographs of his paintings well into his 90s] Nonetheless, he has exhibited often in his home country and his work has been re-engaged with a global New Zealand cultural context through his growing connections with expatriate New Zealanders.

While Douglas feels that his ties are now closer to France than to New Zealand, as we talk we enjoy a bottle of Matawhero Gewürztraminer from Gisborne. The wine is a gift from the New Zealand Embassy and, at the end of our discussion, we are joined by an expat New Zealand photographer, another of Douglas’s expanding New Zealand network in Paris – proof of the internationalism that informs this timeless artist’s world.

To read more about Douglas MacDiarmid’s fascinating journey through life Buy your copy of Colours of a Life – the life and times of Douglas MacDiarmid by Anna Cahill (2018)