In his own image – how Douglas MacDiarmid sees himself

Self-portraits are amongst the hardest, most exacting form of art, especially if the painter is honest. Unlike the snapshot selfies of the me generation, these images are usually less driven by vanity and more by practical or analytical purposes.

When no model is available, there is always that face the painter knows best – the one who doesn’t complain about the results. It’s a way to test or publicly advertise their skill, or even to chart their progress, capturing the basics of the eyes, nose, mouth, hair in an immediately identifiable way. After all, if you can’t capture the essence of your own self, how can you ever to capture the spirit of somebody else?

For Douglas MacDiarmid, the creative process has always been one of self-discovery. “All I can really know is myself, and all I can really express is that. I am not primarily concerned with what is new, only what comes as near as humanly possible to being faithful to that excruciating balance between feeling and vision,” he said a few years ago.

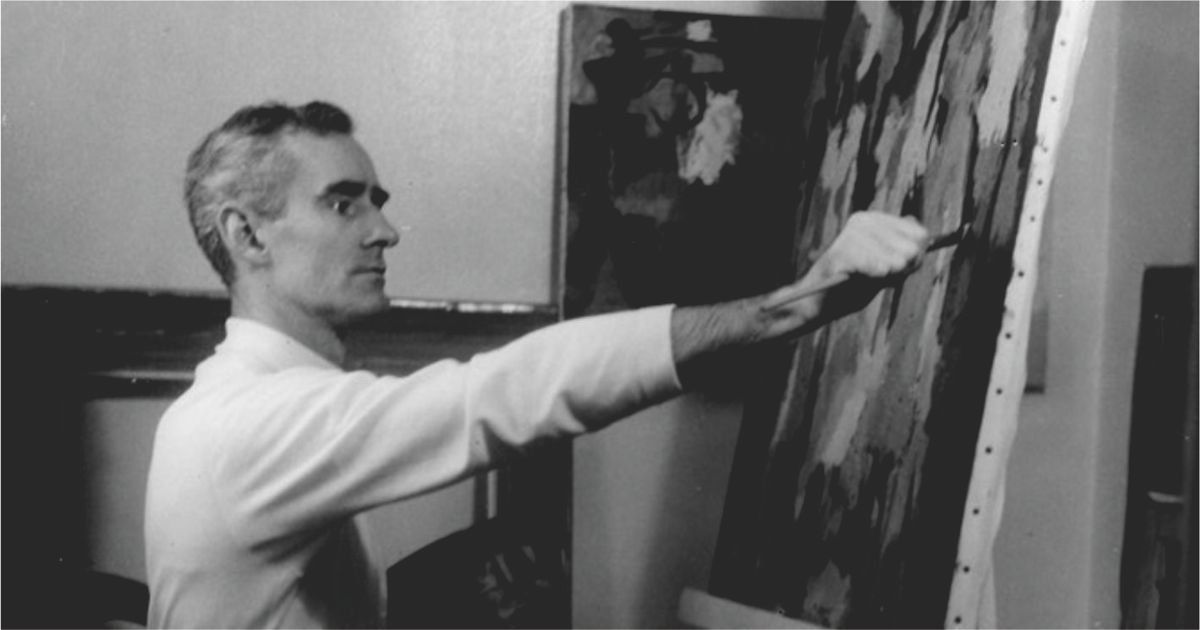

And more recently, “The very fact of painting cuts us down to size every day of our lives. It all boils down to the impossible struggle to surpass oneself, which grows progressively more imperative and more difficult with every added years’ experience.”

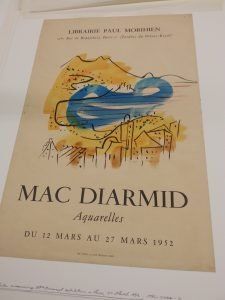

Self-portraits have been part of Douglas’ diverse repertoire since his student days. Here is a sample of less familiar Douglas’ self-portraits over the decades, starting with a young man trying out life, as depicted in this 1945 oil painting, whereabouts unknown, that was one of his early attempts to set himself on canvas.

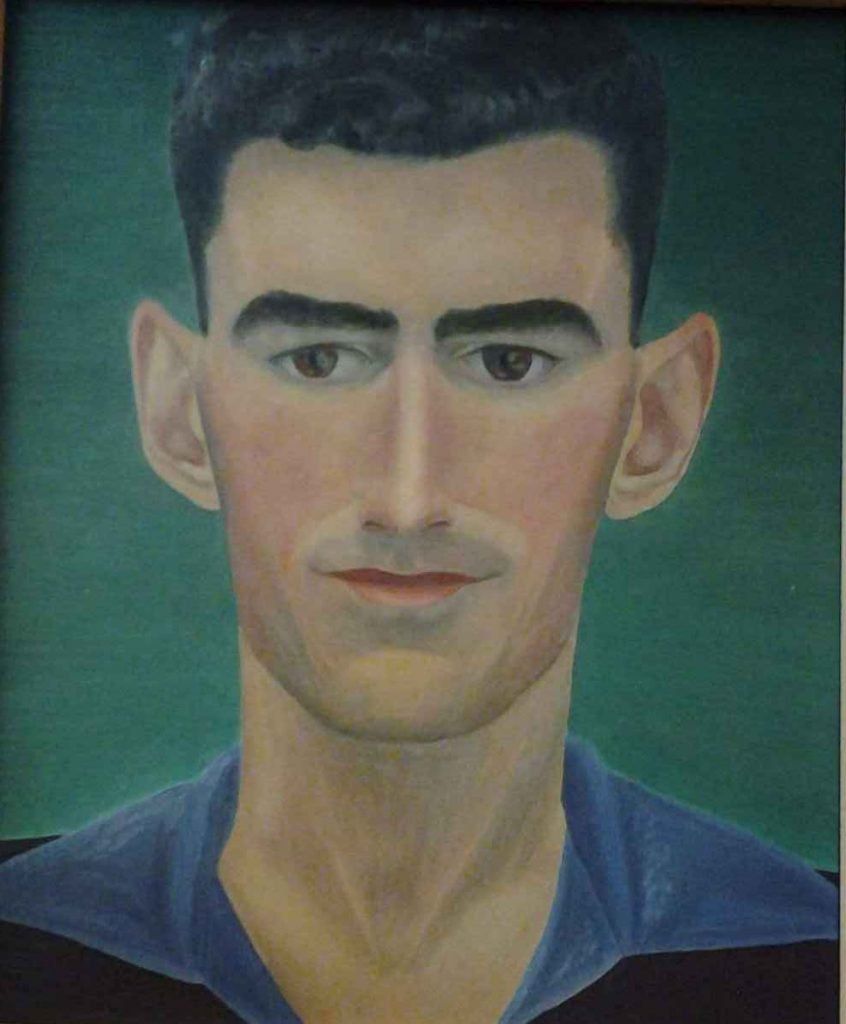

As his early portraits of other people demonstrated, he was a quick learner, soon depicting himself with much greater assurance than in this 1944 oil painting, from the Alexander Turnbull Library Art Collection, affectionately known as the ‘wingnut ears’ picture.

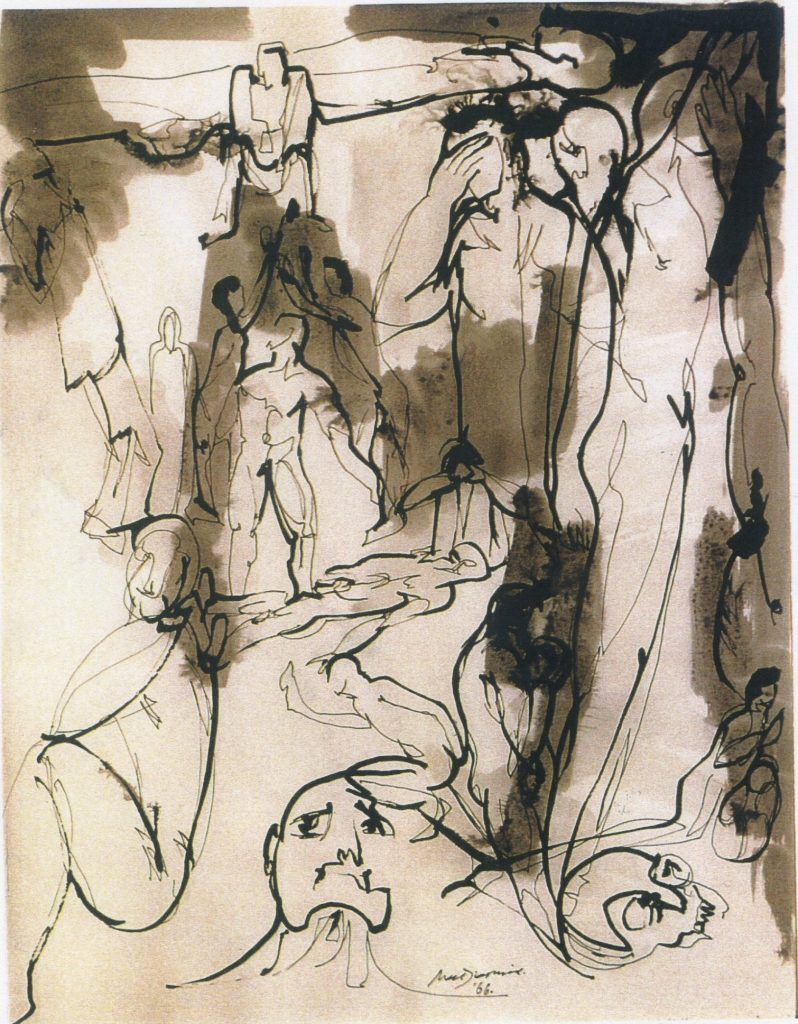

In a playful mood, this 1966 ink drawing is hard to beat as a statement of changing attitudes and states of being. Douglas was experimenting with continuous line drawing, and made a painting of human forms flowing through contrasting variations which he called The self from day to day – everything from goofy to dead.

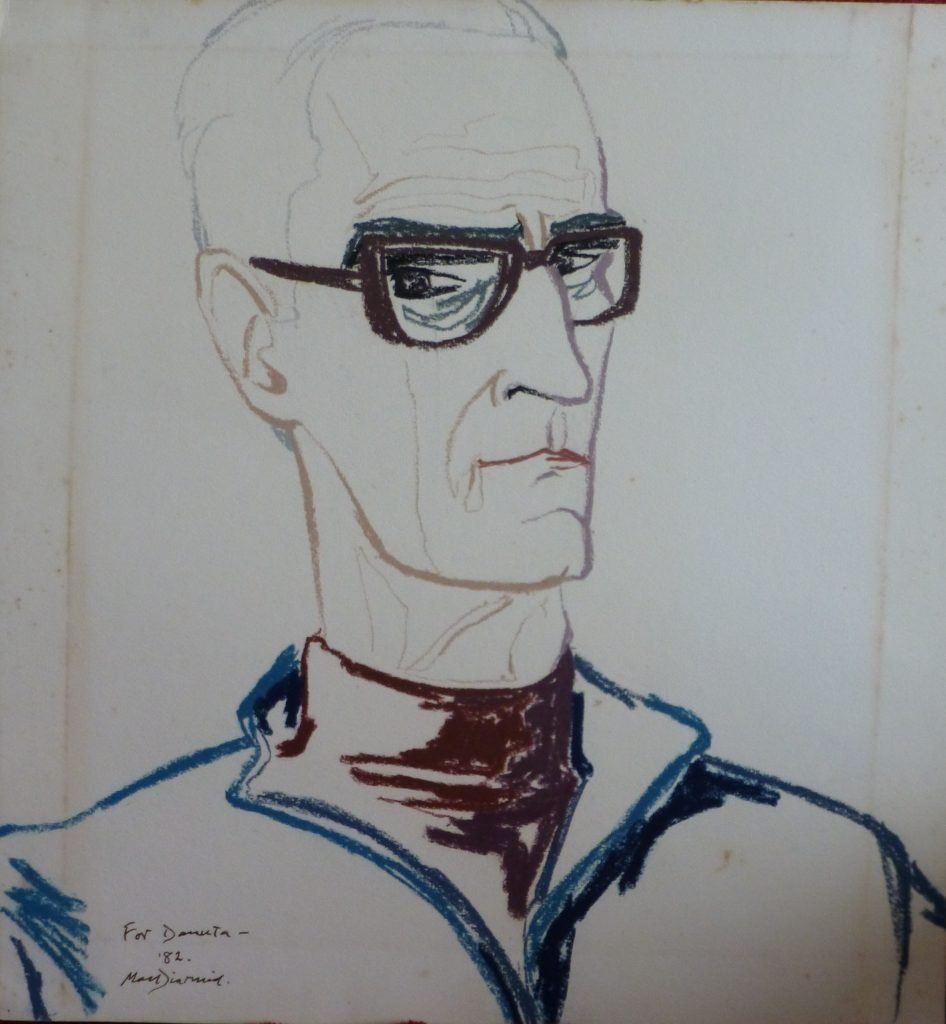

A pastel image made for a much-loved friend,

For Danuta

(1982) shows the painter in maturity, and is still treasured by her family, among the MacDiarmid works on the walls of their house in America.

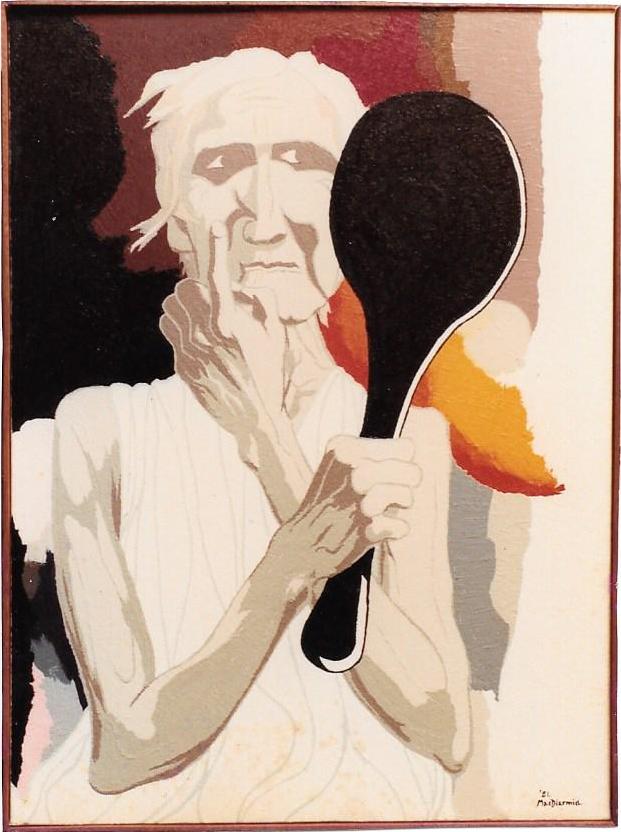

It could be argued that

TIME: Age 1983 is not a self-portrait, but it is a representation of Douglas. “When people ask me who is the woman with the mirror, I am reminded of the great 1856 classic novel, Madame Bovary. It caused a scandal and the author Flaubert was taken to court for his portrayal of this character – how dare he expose any woman in this way and betray all her secrets. When Flaubert was asked who the model was, he replied ‘C’est moi!’ I didn’t have a model for my painting, so I sat for it myself. The old woman with the mirror, it is I.” And the mirror was a memory of a beautiful black ebony framed hand mirror his Mother used.

In a nostalgic reverie, Douglas returns to childhood in

The Aunt from Scotland

2002, showing himself as a very small boy reacting in awe to the first sight of the tall, commanding figure of Margaret McKenzie visiting New Zealand from the ancestral homeland. Douglas was 80 when he painted this scene that had stayed with him all those years.

To read more about Douglas MacDiarmid’s fascinating journey through life Buy your copy of Colours of a Life – the life and times of Douglas MacDiarmid by Anna Cahill (2018)